Archives

now browsing by author

Eat It Dirty

Two words: gut flora.

A pair of articles that appeared recently in the New York Times provide some good leads on why our reactions to food may be changing, why people eating the same diet today may be reacting to it differently than people did 40 years ago.

First, Michael Pollan’s latest piece in the New York Times Magazine, Some of My Best Friends Are Germs, dives into the hidden world inside us and on us: the 100’s of trillions of bacteria that inhabit our gut, our skin and everywhere in between.

First, Michael Pollan’s latest piece in the New York Times Magazine, Some of My Best Friends Are Germs, dives into the hidden world inside us and on us: the 100’s of trillions of bacteria that inhabit our gut, our skin and everywhere in between.

I won’t do it justice, but I’ll give it a shot anyway: our bodies are chock full of microbes. In fact, for every one human cell in your body, there are about 10 non-human microbes. Many of these microbes have co-evolved with us, and play important roles in our health.

Small example:

We’ve known for a few years that obese mice transplanted with the intestinal community of lean mice lose weight and vice versa. (We don’t know why.) A similar experiment was performed recently on humans by researchers in the Netherlands: when the contents of a lean donor’s microbiota were transferred to the guts of male patients with metabolic syndrome, the researchers found striking improvements in the recipients’ sensitivity to insulin, an important marker for metabolic health. Somehow, the gut microbes were influencing the patients’ metabolisms.

And also:

Most of the microbes that make up a baby’s gut community are acquired during birth — a microbially rich and messy process that exposes the baby to a whole suite of maternal microbes. Babies born by Caesarean, however, a comparatively sterile procedure, do not acquire their mother’s vaginal and intestinal microbes at birth. Their initial gut communities more closely resemble that of their mother’s (and father’s) skin, which is less than ideal and may account for higher rates of allergy, asthma and autoimmune problems in C-section babies: not having been seeded with the optimal assortment of microbes at birth, their immune systems may fail to develop properly.

Much research has gone into one microbe in particular, Helicobacter pyolori (H. Pylori):

The microbe engages with the immune system, quieting the inflammatory response in ways that serve its own interests — to be left in peace — as well as our own. This calming effect on the immune system may explain why populations that still harbor H. pylori are less prone to allergy and asthma. Blaser’s lab has also found evidence that H. pylori plays an important role in human metabolism by regulating levels of the appetite hormone ghrelin. “When the stomach is empty, it produces a lot of ghrelin, the chemical signal to the brain to eat,” Blaser says. “Then, when it has had enough, the stomach shuts down ghrelin production, and the host feels satiated.” He says the disappearance of H. pylori may be contributing to obesity by muting these signals.

And H. pylori is nearly extinct in the Western gut.

So the various organisms that live in us and on us help us digest our food, help teach our immune system which microbes are friend and which are foe and perform other key functions in helping us live the way we evolved to.

So, what’s changed?

Well, there’s the obvious: “Children in the West receive, on average, between 10 and 20 courses of antibiotics before they turn 18,” according to Pollan. Each of those treatments carpet bombs the gut, ridding it indiscriminately of both beneficial and dangerous colonies of microbes. Some colonies bounce back, others don’t.

Of course, prescribed antibiotics taken directly are only part of the problem: all non-organically raised farm animals in the United States receive low doses of antibiotics their whole lives (see this Michael Pollan interview for why that is), so if you’ve eaten meat, you’ve been taking low doses of antibiotics every day of your life, further stressing your internal ecosystem.

But Pollan brings up a whole other set of influencers: the care and feeding of your microcolonies. The bacteria in your body need particular nutrients to thrive, as well. This starts early:

For years, nutrition scientists were confounded by the presence in human breast milk of certain complex carbohydrates, called oligosaccharides, which the human infant lacks the enzymes necessary to digest. Evolutionary theory argues that every component of mother’s milk should have some value to the developing baby or natural selection would have long ago discarded it as a waste of the mother’s precious resources.

It turns out the oligosaccharides are there to nourish not the baby but one particular gut bacterium called Bifidobacterium infantis, which is uniquely well-suited to break down and make use of the specific oligosaccharides present in mother’s milk. When all goes well, the bifidobacteria proliferate and dominate, helping to keep the infant healthy by crowding out less savory microbial characters before they can become established and, perhaps most important, by nurturing the integrity of the epithelium — the lining of the intestines, which plays a critical role in protecting us from infection and inflammation.

Which brings up the second article, Breeding the Nutrition Out of Our Food, which shows how the foods that we eat, even the whole food produce, has become gradually less nutritious over time, as we’ve bred it for flavor and sweetness.

Phytonutrients are a set of compounds produced in plants that have generally positive health effects for humans: they’ve been shown to reduce the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and dementia, to name a few.

And they’ve been disappearing from our foods.

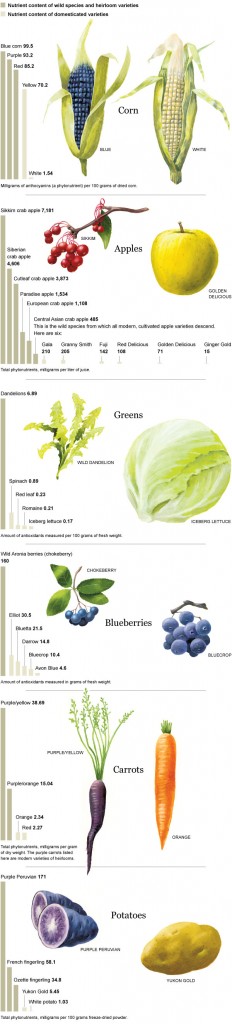

While I’d love to use this data to slap my GMO-loving friends in the face, the truth is it goes back much further than the 20th century. Since the beginning of agriculture, we’ve been selectively breeding our produce for sweetness and taste over the presence of phytonutrients (which often come with bitterness). Wild dandelions, for example, have seven times more phytonutrients than spinach. Purple potates have 28 times the cancer-fighting anthocyanin than russet potatoes. The ancestors of apples have a 100 times the phytonutrient content as most modern apples.

But we’ve certainly accelerated the trend: the sweet, juicy corn that we eat today simply didn’t exist a mere 200 years ago. Iceberg lettuce has about 1/5th the phytonutrients as spinach. The attractive orange variety of carrot that is the only kind available in most supermarkets has 1/7th the phytonutrients as their purple/orange cousins and less than 1/15th as much as their purple/yellow cousins.

So the food that we feed ourselves has been changing, and the food that we feed the microbial ecosystem that helps us digest our food has changed. Are you surprised that our reactions to food have changed?

So what are we supposed to do with all this? Here’s my take-away:

- Unless you’re a doctor scrubbing in, ditch the anti-bacterial soap and the bleach on everything. Let it grow.

- Consider giving your natural immune system a chance to deal with infections before resorting to antibiotics.

- Look for heirloom and wild varieties of fruits and vegetables.

- Eat root vegetables with the skin on: the skin is where most of the nutrients and microbiota are.

- Seek out fermented foods: kombucha, kimchi and raw-milk cheese, to name a few. They’re alive!

And there was one more passage from Pollan’s article that stuck out for me:

The data helped demonstrate that the microbial communities of couples sharing a house are similar, suggesting the importance of the environment in shaping an individual’s microbiome. Knight also found that the presence of a family dog tended to blend everyone’s skin communities, probably via licking and petting.

So, just as vaginal birth can help pass microbiota from mother to child, establishing a healthy ecosystem, the family dog licking everyone’s hands helps spread the beneficial microbiota from person to person within a household.

Don’t have a dog? Kiss your baby!

Autistic for a Day

People often remark how articulate and clear-spoken our four-year-old son Zevin is. So, when just moments after the doctor pricked his skin with the needle, Zevin became a different person, clapping and flapping his hands as he tried to explain something, and making a high-pitched “eeeee” noise, it was both startling and disturbing. Normally a remarkably coordinated four-year-old, he began bumping into tables as he stumbled around the room. His cheeks and ears flushed and his lips became bright red.

And while this autistic-like symptoms were exaggerated and (thankfully) temporary, it was easy to see that this was a compressed version of behaviors we’d seen in varying spells in him before: the tense, aggressive energy, a whole different animal than the cheerful boyish tumult we welcomed.

We were in the allergists office at Northwest Center for Environmental Medicine, following up on a hunch that Zevin had more than just gluten intolerance. This was the second of three allergy tests for the day, but the most striking. The first was for soy, this second one for corn, and eggs was yet to come.

The morning long test began with a base-line pinprick: a tiny shot of glycerin in his upper shoulder, the control dose to ensure that any reactions we saw were not just due to needles or some other aspect of the test. Then came a dose of the allergen, followed by a ten minute observation of his behavior and skin reactions (at right), then another reduced dose of the allergen and more observation, and the cycle was repeated until the “no reaction” dose was reached.

The morning long test began with a base-line pinprick: a tiny shot of glycerin in his upper shoulder, the control dose to ensure that any reactions we saw were not just due to needles or some other aspect of the test. Then came a dose of the allergen, followed by a ten minute observation of his behavior and skin reactions (at right), then another reduced dose of the allergen and more observation, and the cycle was repeated until the “no reaction” dose was reached.

His reaction to corn wasn’t a complete surprise: we’d already noticed that following meals with corn-based ingredients, he seemed to act wilder, obstinate and harder to reason with. We suspected it was corn, but it was so hard to tell because corn and corn derivates are ubiquitous in the American diet: 40% of all packaged goods contain corn derivates. As Michael Pollan puts it: if you are what you eat, most of us are corn.

More surprising was his reaction to eggs, which I’d personally been pushing on him as “the perfect protein”: he became limp, quiet and withdrawn, draping himself over Michelle. It would have been easy to believe he was just worn out from his corn-fed frenzy, but we knew him well enough to know that even an hour of frenzy wasn’t enough to wear him out this much.

Thankfully, the symptoms from the tests subsided, and we settled back at home to start planning next steps: a restricted diet and a course of desensitization (see The Allergy Buster in the New York Times) that would hopefully allow Zev to return to normal eating soon.

But as we ran over the clues we’d had over the years that some food allergy might be impacting Zev’s behavior and development, we kept coming back to an awful thought: what about all the kids who suffered from similar allergies whose parents didn’t know?

Imagine that your child has behavioral issues: maybe they’re acting out or maybe they’re withdrawn, maybe missing development milestones, having trouble with speech or aggression, or seem to be overly sensitive to stimulus and noise. Maybe you chalk it up to “that’s just the way my kid is”.

But maybe it isn’t. Maybe the food you’ve been eating yourself, day after day while you nursed, and then the food you’ve served for breakfast lunch and dinner, is causing a reaction in their body, in their brain, that is changing their behavior and development from what it “should be” to what “it is”.

The numbers of children diagnosed with autism, ADHD and food allergies have all been skyrocketing (see Diagnoses of Autism on the Rise, ADHD Seen in 11% of US Children, Food Allergies Among US Children). Some people think it’s just better (or overaggressive) diagnostic techniques, others think something has changed in our environment or food pipeline, or maybe some epigenetic shift caused by who knows what. It’s easy to see, though, how a persistent, system-wide allergic reaction in the body, or anything that changes how key nutrients are absorbed, could impact the brain development of a growing child.

The symptoms Zev was experiencing in that doctor’s office were a mixture of what would ordinarily be classified as autism or as ADHD: flapping hands, sub-par motor control, difficulty in focusing, fits of irrational anger. His experience there was sudden and stark, because of the dose and the subcutaneous way it was administered, but a child with a similar allergy who ingested the allergen (corn, in this case), day in and day out, would experience a low-grade version of these symptoms all the time. Without the contrast to “normal” behavior, it would be easy to assume that that’s simply “the way my child is” and ignored.

The symptoms Zev was experiencing in that doctor’s office were a mixture of what would ordinarily be classified as autism or as ADHD: flapping hands, sub-par motor control, difficulty in focusing, fits of irrational anger. His experience there was sudden and stark, because of the dose and the subcutaneous way it was administered, but a child with a similar allergy who ingested the allergen (corn, in this case), day in and day out, would experience a low-grade version of these symptoms all the time. Without the contrast to “normal” behavior, it would be easy to assume that that’s simply “the way my child is” and ignored.

Or maybe worse, assume he had a disorder, and medicate him.

In the short week since the test, and since we eliminated corn, soy and egg from his diet, we’ve already seen a calmer, more thoughtful, well-reasoned child (except when he’s tired, he is a four-year-old, after all). It’s been hard, but weighed against a lifetime of the alternative, we know it’s been worth whatever we have to do.

But we grieve for all the kids out there who may be on a path to special ed classes, medication or just tense, angry relationships with their frustrated parents.

What’s been most amazing is the number of people who seem to know that food allergies might be at the root of their children’s behavioral issues, but are unwilling to find out more, or to do something about it.

“I just couldn’t do it, it’s too hard to totally change the way we eat,” we hear, over and over.

I get it. Honestly, if it weren’t for Michelle, I wouldn’t be able to do it either. I’m not “doing it”. I only eat well, and Zevin only eats well, because she does the hard work to make it easy. And I’m grateful for that.

Sometimes I wonder: what if a doctor in a white lab coat told people that there was this medicine their child could take, and it would cure their kid’s ADHD or autism, and the medicine was delivered in this special food, but it was important for the medicine to work, that they not eat anything except the special food. Would people do it?

Of course, the ‘medicine’ is just good, wholesome food, without corn or gluten or dairy or whatever the kid was allergic to.

But maybe the key to that story is the doctor “giving them the medicine”. Most people don’t know where to start when it comes to remodeling their diet. I hope that’s what Michelle’s work (and workshop) will help address. If it can help even one more child live a different, better life than he would have, it’s well worth it.

[5/10/2013: I should clarify, since it may have been ambiguous, that Zevin does NOT have autism or ADHD, not even a little bit. He does has food allergies that we’ve been carefully studying and addressing. What I was hoping to convey is that based on his reactions to foods, it might have been mistaken for something larger, and, if left unaddressed, could possibly have led to something more permanent. And I hope that no child with a similar make-up is given a mistaken diagnosis.]

Juice Brawl

The Juice Bar Brawl, a New York Times article on the new juice bar craze that’s taken root in New York and LA, caught my eye, partly because it’s clear the entire industry has taken note of (but missed the core point of) my Drink My Salad article.

The Juice Bar Brawl, a New York Times article on the new juice bar craze that’s taken root in New York and LA, caught my eye, partly because it’s clear the entire industry has taken note of (but missed the core point of) my Drink My Salad article.

As you may remember, my recommendation for those, like me, too lazy to actually sit and, you know, eat vegetables, was to try throwing them in a blender with a bit of carrot juice and coconut water (for liquidity) as well as raspberries and mint (for sweetness and zing).

Apparently, the LA / NY scene is on to the same idea:

Half a decade ago, most people who were found guzzling and gushing about juice — not grocery store O.J., but the dense, cold-pressed stuff that is made by pulverizing mounds of ingredients like kale, beets, ginger, spinach and kohlrabi — were either zealots from the raw-food fringe or Hollywood celebrities who believed that a “juice cleanse” would nudge their toned bodies even closer to radiant perfection.

But along the way, more people started drinking it. And for consumers and entrepreneurs, a realization took hold: juice did not have to be part of a challenging, expensive cleanse. It could simply be lunch. Suddenly, cold-pressed juice morphed from a curiosity to an industry.

But wait! Not so fast! There’s a big difference between eating the whole, blended vegetable, and just drinking its juice: the fiber!

When you juice a vegetable, you leave the fiber behind. But the fiber is a key component in modulating the way your body absorbs sugars. If you extract just the sweet juice from vegetables and leave the fiber behind, you end up with a sugar rush: the same kind of thing you get from drinking a soda. Rapid fluctuations in blood sugar has been tied to a variety of health ailments, including Type 2 Diabetes. Fiber also lowers bad LDL cholesterol, promotes heart health and gives you the feeling of satiety that helps keep your mind away from unnecessary snacking.

And don’t even start talking Jamba Juice, which adds corn syrup to their “smoothies”, unless you really want to get me started.

When Michelle talks about “whole foods”, it’s usually set in contrast to “processed foods”. But here, it also means: “the WHOLE food”, as in, eat the whole thing, rather than strip-mining just the sweet parts you like.

Drink My Salad

I’m lazy. How lazy am I? I’m too lazy to chew.

Seriously, I enjoy a good salad: they taste great, they make me feel great, but OMG, they take so long to eat. Take a bite, chew, chew, chew. Take another bite, chew, chew, chew.

“Hey Jordan, we’re going out, wanna come?”

“Nope, sorry, I gotta stay home and masticate.”

Fortunately, I’ve found a solution: drink my salad. All the yumminess and healthy goodness of a salad, but you can slurp it down on the go!

Here’s my recipe. As noted, you should think of this as a starting point. Personalize it. One bonus of the ingredients that I use is that virtually all of them can be found at Trader Joe’s, making for an easy shopping trip. I’ll make a big batch, freeze some of it, drink it over several days, then leave my frozen jar in the fridge to defrost for the next day.

[bigoven-recipe url=”http://www.bigoven.com/recipe/476423/salad-smoothie”]

Note: this is a salad in a blender, not be be confused with the sugar syrup they sell at places like Jamba Juice.